Here is a place of history. It is a pleasant side trip on the way to Saint Michael’s or,Oxford, Maryland. You can go for the history or buy some fresh ground grains as people did long ago. I will include some recipes.

The Mill was important during George Washington’s time.

One of the oldest continuously operating water Powered Mill in the United States

The Old Wye Grist Mill is located in the town of Wye Mills, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. It is the oldest continuously operated water powered grist mill in the U.S. and the oldest commercial structure in continuous use in the State of Maryland. Founded in 1682, the has a long and fascinating history and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. During the Revolutionary War, the Mill was called upon to provide flour for George Washington’s troops.

Grist is grain that has been separated from its chaff in preparation for grinding. It can also mean grain that has been ground at a gristmill. Its etymology derives from the verb grind.

Grist can be ground into meal or flour, depending on how coarsely it is ground. Maize made into grist is called grits when it is coarse, and corn meal when it is finely ground. Wheat, oats, barley, and buckwheat are also ground and sifted into flour and farina. Grist is also used in brewing and distillation to make a mash.

Bay Journal Article

Bay Journal

https://www.bayjournal.com/article/old_wye_grist_mill_still_grinding_after_all_these_years

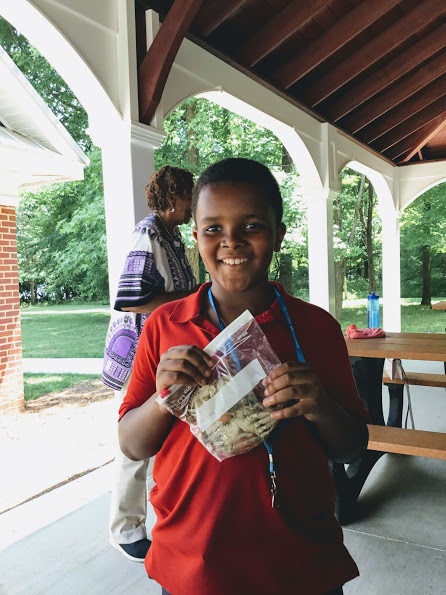

Recently, en route to Saint Michael’s and Oxford, we made a stop at the “Old Wye Mill” in Wye Mills. We arrived just as this historic mill was closed but Vic talked his way in and we were able to purchase holiday offerings and the week’s run of corn meal, grits or flour. We grinned all the way to our destination. We were thinking of cornbread.

Back in the 1620s, corn was a lifesaving grain. Early settlers learned to plant and harvest corn, and then use it in stew dishes such as succotash, in puddings, and in various baked and fried breads. Nowadays, modern recipes will give you a fluffy texture and sweet tasting bread. Here are three recipes to taste and explore! Use the Three Kinds of Colonial Cornbread activity to learn how to make corn pone, johnnycakes, and spoon bread. Download free activity.

I couldn’t resist sharing a classic, easy side dish recipe for old-fashioned Virginia Spoon Bread! The Delmarva area and many other parts of the South were called the hot bread zone, recipes interchangeable. Spoon Bread is a special kind of moist, custard-like cornbread that you can scoop with a spoon.

HoeCake?

The modern johnnycake is found in the cuisine of New England,[3] and often claimed as originating in Rhode Island.[4] A modern johnnycake is fried cornmeal gruel, which is made from yellow or white cornmeal mixed with salt and hot water or milk, and sometimes sweetened. In the Southern United States, the term used is hoecake, although this can also refer to cornbread fried in a pan .

Johnnycake (also called journey cake, spider cornbread, shawnee cake or johnny bread) is a cornmeal flatbread. An early American staple food, it is prepared on the Atlantic coast from Newfoundland to Jamaica.[1] The food originates from the indigenous people of North America. It is still eaten in the West Indies, Dominican Republic, Saint Croix, The Bahamas, Colombia, and Bermuda[2] as well as in the United States and Canada.

| A Johnnycake in a cast iron fry pan | |

| Alternative names | Jonnycake, shawnee cake, hoecake, johnny cake, journey cake, and johnny bread |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | United States |

| Main ingredients | Cornmeal |

| Cookbook: Johnnycake Media: Johnnycake |

One of the better byproducts of the nationwide fascination with Southern food is that Southern ingredients—grits, cane syrup, sorghum, and, most especially, good cornmeal—are getting easier to find outside the South. What this means for non-Southern cooks is that you can quit diluting your cornbread with tons of flour and sweetener, and start making cornbread with some bones.

You can, in other words, make hoecakes.

The first challenge with hoecakes is getting across what they actually are. Though they look something like pancakes, they are not pancakes, which are made pliable and fluffy with leavening, milk, eggs, and flour. Hoecakes could also, at first sight, pass as corn tortillas or arepas, both made with meal from pre-treated corn. But looks are deceiving.

A hoecake is cornbread made minimalist—a thin, unleavened round made from the simplest batter (cornmeal, water, and salt), crisp at the edges, glistening on both sides from the fat it was fried in, golden in patches. Inside, it’s dense but creamy, a foil for its best partners—creamed corn, silky braised greens, honey. A hoecake should be sturdy enough to work as a shovel for whatever is on the plate, but delicate enough to be appealing on its own.

Hoecakes got their name from the slave practice of cooking them on field hoes in the fireplace before going out into the fields in the morning. My family often cooks them as a part of a meal with local fish.

.

Hoecakes didn’t come about because someone thought a bread made of cornmeal, fat, and water, sounded like a riot in the pan (although if you’re doing it right, it is). The most primitive family of cornbreads—generally called pone, of which hoecakes are just one example—probably wouldn’t have persisted in early American cooking had there been much more for cooks to work with. As colonists saw it, corn was just a crude, ill-behaved substitute for the wheat flour they were accustomed to. Its dough was unwieldy and stubborn, unwilling to respond to yeast or other leavening agents, and it produced dense, earthy-tasting breads beloved by few. In The Story of Corn, Betty Fussell recounts the colonial cook’s perception of cornmeal batter as “the sad paste of despair.”

But over time that sad paste of despair became a point of regional pride. And while there are now innumerable variations on corn-based bread, hoecakes show how far some of those variations (most notably, ahem, those north of Virginia) have strayed from their origins, becoming light, fluffy, and sweetened. They are often more cake than bread, and less about the corn than the ingredients accompanying it. Hoecakes celebrate the flavor of corn without fanfare. Once you get the hang of making them, they are a tasty, no-nonsense response to hunger, as they always have been.

To ensure your hoecakes make it out of the pan intact, it’s essential to use boiling water in the cornmeal mixture. Not only does it encourage greater release of flavor from the cornmeal, it ensures the cornmeal will soak up the water properly; otherwise you’ll be dealing with a loose slop that’s prone to break apart in the pan.

It’s also crucial not to add too much water—hoecakes should have a little heft, so you’re aiming for something like a wet dough (or a thick batter). Linton Hopkins, who occasionally serves hoecakes at Restaurant Eugene in Atlanta, advised me on this point. “Once you get something like a pancake batter, that’s when you get in trouble,” Hopkins says. He also advises letting the dough rest for a bit after combining.

Start small at first. My granddad makes one giant ½-inch hoecake in a 12-inch aluminum skillet, but this is quite a feat, as far as I can tell. Easier to manage is using a nonstick or cast-iron skillet to prevent sticking, and making fewer, smaller, hoecakes—I’ve found 6 inches is a good target diameter. Make them as small as you want; you’ll get more crisp crust the smaller you go.

Finally, use good cornmeal. Please. There are so few ingredients here that it is a waste of effort to use anything that’s been sitting around staling away, ready to lend your hoecakes all the flavor of sawdust. Freshness is paramount, and if you can get your hands on stone-ground, cold-milled grain, even better. White cornmeal is traditional, but yellow cornmeal works just as well.

Hoecakes are best at their warmest and crispiest, but leftovers can be re-warmed in the oven. They make for fine dessert drizzled with cane syrup or crumbled into buttermilk.

Hoecakes

Yield: Two 6-inch cakes (2 to 3 servings)

Time: About 1 hour, partially unattended

1 cup fine-ground white or yellow cornmeal

Scant ¼ teaspoon salt

3 tablespoons peanut oil

1. Bring a kettle of water to a boil. Put the cornmeal and salt in a large bowl, and whisk in 1 cup plus 2 tablespoons of the boiling water. Let rest about 10 minutes.

2. Stir in 1 tablespoon of the peanut oil. The mixture should be just pourable, but thick enough that you’ll need to use a spoon or spatula to help spread it out once it’s in the pan. If it seems too thick, add another tablespoon or two of hot water.

3. Put the remaining 2 tablespoons oil in an 8- to 12-inch skillet over medium heat. When it’s hot, spoon in about half of the cornmeal mixture, and, using a spatula or the back of a spoon, spread it into a round about 6 inches in diameter. Cook until the hoecake is golden around the edges and looks set throughout, about 10 minutes, then begin to loosen the edges with a spatula. When you’ve fully released the hoecake from the pan, gently flip it. Cook another 8 to 10 minutes, then transfer to a plate. Repeat with the remaining cornmeal mixture. Serve warm.

A family member made a Hoecake for me, telling me that it or grits used to be a country breakfast in the history of the family since slavery time.

Sometimes the grits were with butter and bacon.

Grits is a food made from a dish of boiled cornmeal. Hominy grits are a type of grits made from hominy – corn that has been treated with an alkali in a process called nixtamalization with the pericarp removed. Grits are often served with other flavorings as a breakfast dish.

Grits were part of the daily fabric of my breakfast before they were a part of special cuisines. Grits may be yellow or white, fine or course ground.

Southern breakfasts usually consisted of scrambled eggs, bacon, biscuits, and a pot of grits. Sometimes the biscuits were replaced with toast or hoe cakes.

You may want to schedule your visit to see a Grinding.

Grindings: Grindings are the 1st and 3rd Saturday of the month.

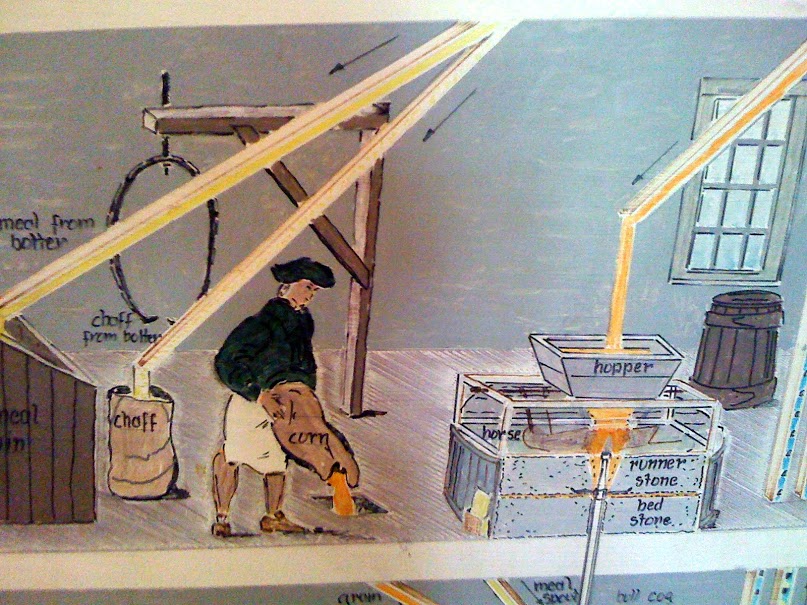

How the corn was ground!

https://garden.org/learn/articles/view/397/

- Recipe: Spoon Bread ( Maryland’s Way)

1 Cup water-ground cornmeal - 2 Cups cold water

- 2 tb butter

- 1 Teaspoon scant salt

- 1 Cup half & half

- 3 eggs

Put corn meal and water over low heat and stir until quite stiff. Melt butter into hot meal then add salt and milk or cream. Beat eggs until very light. When batter is slightly cooled, beat in the eggs. Bake in a well greased baking dish in 350° oven for 45 minutes or until firm.

Recipe adapted from “Maryland’s Way”

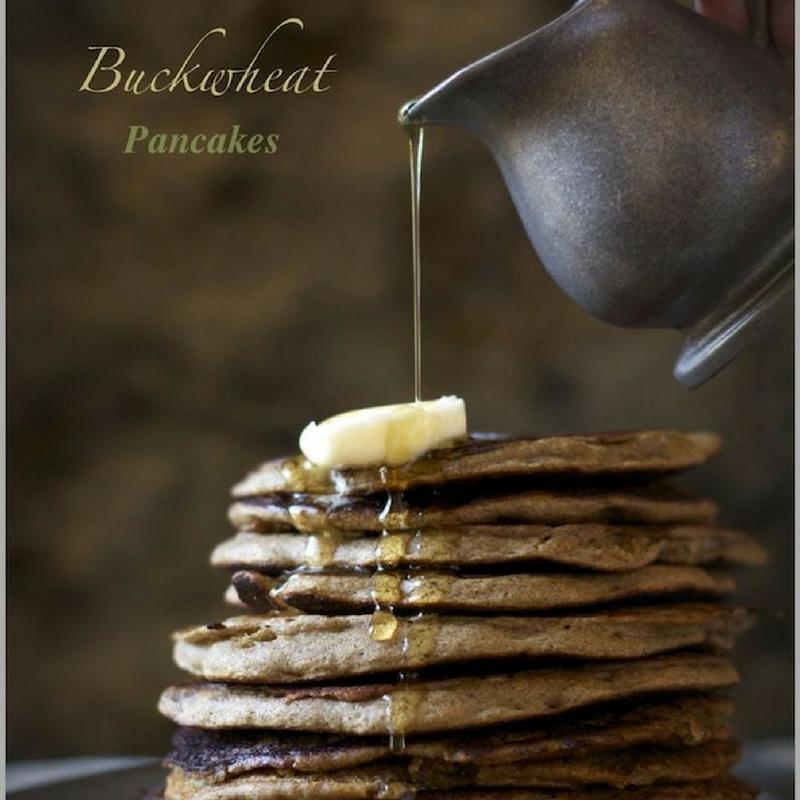

This is buckwheat.It was popular.A little earthy, a little nutty, a little bitter: The flavor of buckwheat can be intense. But roast buckwheat seeds, or mix buckwheat flour with other flours, and the taste is tamed. It’s a taste more of us are getting to know.Besides being gluten-free, buckwheat is a nutritional powerhouse; it helps lower cholesterol; it can fight adult-onset diabetes: “That’s a claim that has been scientifically backed,” he says. It grows well in poor soil and doesn’t need fertilizer, herbicides for weed control or insecticides for pest control. “Very often it’s grown organically.At the grocery store, it comes in several forms. Buckwheat groats are the plant’s hulled seeds. Kasha is groats that have been roasted. Groats and kasha are sold in different grinds, from fine to coarse. Buckwheat flour, the finely milled seeds, can be dark or light, depending on how much of the strongly flavored hull is included.Buckwheat came to America with early European colonists and was most commonly grown in the northeast and northwest of the country. At its peak of production in 1886, buckwheat was most commonly used for flour and animal feed. Major agricultural advances of the 20th century, such as nitrogen fertilizer, increased the productivity of major staple crops like wheat and corn to such a degree that the production of minor rotational crops, such as buckwheat, declined steadily. In was not until the 1970s that buckwheat enjoyed a boost in popularity, and it continues to be a popular gluten free flour option for bakers. According to the UN, in 2016 Russia lead the world in buckwheat production, followed by China and Ukraine (FAOSTAT data, chart courtesy of Wikipedia)

Buckwheat forms the backbone of many traditional dishes across Asia and Europe. Soba noodles are enjoyed both hot and cold in Japan, and in Korea buckwheat flour and potato or sweet potato starch are used to make the traditional noodle dish naeng myun. Italy’s Lombardy region produces pizzoccheri, a type of short, flat ribbon pasta made with buckwheat and wheat flour. Elsewhere in Europe buckwheat flour is used to make galettes, a famed crepe from the Brittany region of France, and in Eastern Europe buckwheat plays a leading role in the pancake like blinis and blintz’s. For many countries in Eastern Europe buckwheat is most commonly used in its whole form, roasted and made into a traditional porridge called kasha – one of the national dishes of Russia.

Heat up the griddle! Here’s another delicious recipe to make at your next family breakfast, brunch, or dinner.

Buckwheat Flapjacks

Ingredients:

- 1 cup buckwheat flour

- 1 1/2 teaspoons white sugar

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- 1/4 teaspoon salt

- 1/4 teaspoon baking soda

- 1 teaspoon cinnamon

- 1/2 teaspoon nutmeg

- 1 1/4 cups buttermilk

- 1 large egg, beaten

- 1/4 teaspoon vanilla extract

- 1 tablespoon unsalted butter, or as needed

Sift together buckwheat flour, sugar, baking powder, salt, baking soda, cinnamon, and nutmeg. Beat buttermilk, egg, and vanilla extract together in another bowl. Pour flour mixture into buttermilk mixture; whisk until batter is thick and smooth. Let batter rest for 5 minutes until bubbles form and batter relaxes.

Melt butter on a griddle over medium heat. Drop batter by large spoonful onto the griddle and cook until bubbles form and the edges are dry, 3 to 4 minutes. Flip and cook until browned on the other side, 2 to 3 minutes. Repeat with remaining batter.

Wye Mills has its own cookbook.

Since the area is also a culinary seafood area, you may want to find the spices , and products that enhance the seafood of the area in

The Maryland Store , it is also hidden away.